A Brief Preface to Finch’s Work

The multimedia elements of this site reflect the range of ways that Finch’s work engaged her contemporary readers and listeners, who knew her work in manuscript, print, or performance, or in all of these forms. Annotations to the featured poems provide analysis and contexts that expose Finch’s engagement with her cultural, political and social contexts.

Writing in an era known for the overtly public and political poetry of Dryden, Swift, and Pope, Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea (1661-1720), articulated a different literary and political authority. From her position as a female aristocrat, once at the center of the court and then for many years a political internal exile, Finch explored the individual’s spiritual condition as inextricable from social and political phenomena.

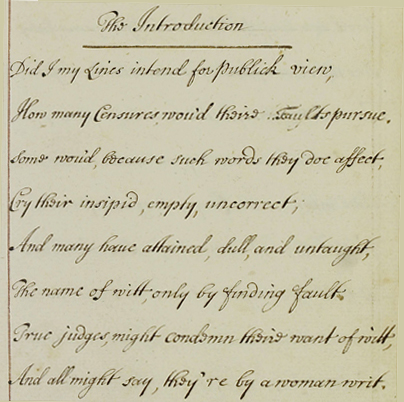

Her interest in affairs of state frequently informed her exposure of patriarchy’s constraints on women and men. Finch’s work participates in the strategies of her contemporaries such as Dryden and Pope—the public speaker who sought to influence state politics, the renovator of classical mythology and pastoral who exposed contemporary mores, the fabulist who satirized state and society, the friend who used the couplet for conversation and exchange, and the wit who made discernment a moral good. But Finch both furthers and deviates from these practices. Although some of her works resemble her era’s poetry of retirement—which from a removed position casts a critical eye on politics and the town—Finch’s poems of retirement reflect her position as a woman and the isolation she endured on the losing side of the revolution of 1688.

Finch’s sensitivity to representation and power relations developed in part from the drastic changes in her circumstances following this revolution. Born Anne Kingsmill, she served from 1682 to 1684 as Maid of Honour to Mary of Modena (wife of the Duke of York, the future James II) and thus began her adult life as a court insider, part of an international group of multilingual women writers and artists. 1 1 The richest sources of information about Finch’s life are Barbara McGovern’s Anne Finch and Her Poetry: A Critical Biography (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992) and W. J. Cameron’s unpublished thesis “Anne, Countess of Winchilsea: A Guide for the Future Biographer” (Victoria College, Wellington, NZ, 1951). I draw from their works in the biographical information in this overview. With the abdication of James II and the installation of William and Mary on the throne, Finch and her husband, Heneage (whom she married in 1684), were exiled from power. On 29 April 1690 her husband was arrested on charges of treason when he and five others were discovered attempting to join James in France. 2 2 See McGovern’s account of this in Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 58. As a Nonjuror who refused to take the oath of loyalty to the new king, Heneage was permanently cut off from political power.

Such extremes in political, social, and financial circumstances—one thinks of her near contemporaries, ranging from Milton and Marvell to Dryden—are at times manifested directly in Finch’s poetry and at other times obliquely in her articulations of political isolation and personal loss. Her religious poetry often connects affairs of state with the suffering soul (see "Psalm the 137th" ), and her lyrics often include critiques of state politics. Although Finch movingly describes her isolation and “retirement” after the Glorious Revolution, it was especially through the circles at Longleat and London that she exchanged work and developed friendships with other important writers of her day, including Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope.

She claimed not to write in the “masculine” domain of satire (“Who e’er of Satyre does my pen accuse / Knows not the stile of my well temper’d muse” [“On my being charged with writing a lampoon at Tunbridge,” lines 1-2]), but Finch indeed produced many satirical poems. Developing her contemporaries’ use of the fable for political critique, she employed the fable to analyze and satirize state and gender politics (e.g., “Love Death and Reputation”). Her often indirect condemnation of political and social ills, conveyed in a range of poetic kinds and tones, enlarges our view of the ways Restoration and eighteenth-century writers reformulated the vocabulary and tones of political discourse.

In addition to the few letters that frame her poems, only a small number of letters by Finch are known to have survived. Even these few show the range of her social, political, and religious concerns (one exhibiting her persistent engagement in the Nonjuring community and her attempt to intervene in the schism in that community through her correspondence with the Reverend Thomas Brett).

Many of Finch’s poems express intimate connections with friends and family. For her the ties between writer and reader were truly collaborative: Heneage and others suggested topics for some of her poems, and she engaged in epistolary dialogues with several poets. That a number of her poems are songs to be set to music (e.g., the two songs on this site, “Persuade me not, there is a grace” and “’Tis strange, this heart within my breast” ) deepens their collaborative nature.

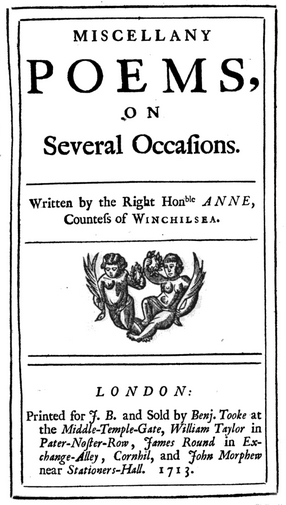

Finch’s work began to appear in print miscellanies as early as 1686. Her poem On the Death of King James. By a Lady , issued twice as a pamphlet in 1701, shows her enduring allegiance to the Stuarts. Finch supervised the publication of her Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions, which was issued in 1713 and 1714. 3 3 Susan Staves describes this collection as “the most accomplished volume of poems published by a woman between 1660 and 1789” A Literary History of Women’s Writing in Britain, 1660-1789 (Cambridge, 2006, 138). This print collection of her work appeared after Heneage had finally, in 1712, inherited the title of the fifth Earl of Winchilsea. 4 4 Finch’s husband is sometimes counted as the fourth and sometimes as the fifth Earl of Winchilsea because the first person to hold this peerage was a woman (see McGovern, 27). The DNB refers to Finch’s husband as the fifth earl. The volume includes a selection of her poems written in the 1680s and 1690s as well as more recent compositions, especially fables, and concludes with her tragedy Aristomenes. Much of her work is found in three manuscript volumes, one housed at the Northamptonshire Record Office, another at the Wellesley College Library Special Collections, and the largest of the volumes at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Jennifer Keith

1 The richest sources of information about Finch’s life are Barbara McGovern’s Anne Finch and Her Poetry: A Critical Biography (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992) and W. J. Cameron’s unpublished thesis “Anne, Countess of Winchilsea: A Guide for the Future Biographer” (Victoria College, Wellington, NZ, 1951). I draw from their works in the biographical information in this overview.

2 See McGovern’s account of this in Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 58.

3 Susan Staves describes this collection as “the most accomplished volume of poems published by a woman between 1660 and 1789” A Literary History of Women’s Writing in Britain, 1660-1789 (Cambridge, 2006, 138).

4 Finch’s husband is sometimes counted as the fourth and sometimes as the fifth Earl of Winchilsea because the first person to hold this peerage was a woman (see McGovern, 27). The DNB refers to Finch’s husband as the fifth earl.