Heneage Finch (1657-1726)

Without further evidence, such as an undiscovered trove of Finch’s letters recounting her editorial relationship with Heneage, we cannot know the degree to which he strictly followed her texts and instructions or shaped the texts in an editorial role. If he did edit her work, then, given her era’s norms for gender decorum, particularly in marriage, we cannot know with certainty how much Finch desired or submitted to her husband’s participation. We do know, however, that for a husband in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England to devote so much time to transcribing his wife’s work remarkably overturns conventional gender roles in that era. References in the poems to her happy marriage and to Heneage’s encouragement of her writing suggest Finch’s satisfaction with his roles as amanuensis and editor; see, for example, on this site Finch’s “A Letter to Dafnis April: 2d: 1685.” The corrections in her hand seen in the Folger folio manuscript, which was transcribed by Heneage, imply that she approved his role while retaining her authorial prerogative to correct his transcriptions. Manuscript revisions and corrections demonstrate repeatedly Heneage’s devotion to ensuring that copies of Finch’s work were accurate: we see in his hand painstaking alterations in every manuscript volume he transcribed.

When Finch’s work was finally collected in the print volume Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions (1713), when she was in her early fifties, Heneage entered in his own hand additional errata lists to some of the print volumes and even transcribed some of these corrections to pages within the volumes. Heneage continued to concern himself with the accuracy of his wife’s work even after her death in 1720: we find him listing errata, not printed in the 1713 volume, in his diary in 1723. Because of his role in the transmission of Finch’s work, the closer we try to approach a traditional notion of the authorized text the more that text becomes a social one, especially informed by her relation with Heneage.

Soldier and Courtier

Heneage Finch was the eldest surviving son of Sir Heneage Finch, third earl of Winchilsea

(1628-1689), a formidable courtier and diplomat who served as ambassador to Turkey

from October 1660 to March 1669. The third earl’s eldest son and heir, William,

Viscount Maidstone, had died in 1672 fighting aboard the Royal Charles during the

naval battle of Solebay, leaving a widow and two young children, one of whom would

inherit the family’s title and estate in Kent.

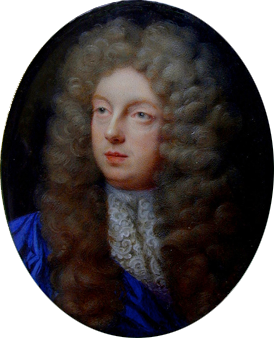

Portrait of James, Duke of York, as Lord High Admiral, by Henri Gascar (1635-1701), painted circa 1675.

The younger Heneage had been trained

to be a courtier and soldier. A captain of the Coldstream Guards, he was appointed

a groom of the bedchamber to James, Duke of York (future James II), in 1683 after

serving in various military and political posts in Kent. Finch indirectly commemorated

Heneage’s military service and support of James in her translation of the French

epitaph of Marshall Turenne, under whom James fought before the Restoration; see

on this site Finch’s

“Under the Picture

of Marshall Turenne”

. Awarded an honorary degree of doctor of civil laws

by Oxford when he visited with James and Mary in May 1683, Heneage seemed destined

for a distinguished career.

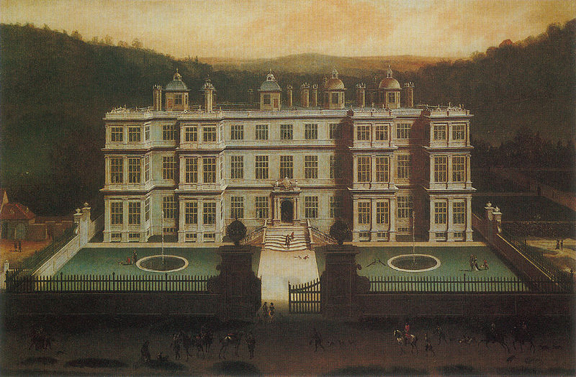

At court, he met Anne Kingsmill, the woman he would marry, who arrived there in 1682 to serve as Maid of Honor to Mary of Modena, James’s second wife. Although in “A Letter to Dafnis,” Finch claims that Heneage had to overcome her reluctance, their marriage license is dated May 14, 1684, and their wedding took place the next day.11 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 29. As a widower forty years later, Heneage would write in his Riders (1723) British Merlin diary next to the date of May 14, “A blessed day.”22 MS F.H. 282 in the Northamptonshire Record Office. After their marriage Finch resigned from her position as Maid of Honor, but the couple remained at court, residing in Westminster Palace after Heneage took part in the coronation of James II in April 1685 as one of the Queen’s canopy-bearers, at her request.33 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 30. Finch’s marriage created a new web of kinship ties and associations reflected in her verse. Most important were Heneage’s immediate family. His father resided at the family’s seat at Eastwell in Kent with his fourth wife, Elizabeth Ayres, several children, his two grandchildren, and his late son’s widow, Elizabeth Wyndham. Her son Charles (1672-1712), Heneage’s nephew, would inherit the family’s title. Heneage’s sister Frances had married Thomas Thynne, viscount Weymouth, and resided at his magnificent estate, Longleat, in Somerset, which the Finches knew well.

Such buoyant times in their early marriage ended with the revolution of 1688/89 and James II’s flight from England. Heneage had held a prominent position in James’s court as Groom of the Bedchamber, lieutenant-colonel, and in 1685, as member of Parliament from Hythe, and his continuing loyalty to the Stuart king placed Heneage and Anne at great risk. In spring 1689 the Finches arrived at Eastwell, probably because of Heneage’s father’s declining health. At the third earl’s death in August, sixteen-year-old Charles Finch became the fourth earl of Winchilsea. The months immediately following the revolution were harrowing for the Finches. Their prospects had been completely reversed, and they suffered the equivalent of internal exile after James’s flight. Matters worsened for Finch when Heneage was arrested at Hythe in April, 1690, while attempting to join James in France. For the rest of the year he was detained in London preparing his defense before his case was dismissed for lack of evidence in late November.44 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 58-60.

Internal Exile

Heneage’s return, late in 1690, reunited the couple at the Finch family manor of Eastwell, now presided over by the young Charles Finch, the fourth Earl of Winchilsea. Significantly, Heneage’s surviving transcriptions of his wife’s compositions all date from after the revolution of 1688/89, thus framing the contexts and suggesting possible motives for the hours, days, and years he dedicated to her poems and plays. Had he not been deprived of his office and livelihood, that is, had he capitulated like so many other members of James’s court and sworn fealty to King William, Heneage would not have had the time to transcribe his wife’s work. Perhaps his political marginalization spurred him to transmit his wife’s literary productions, especially as a way to participate in the social, cultural, and political forces of Stuart loyalists.

The earliest of three manuscript volumes that survive with Heneage’s transcription is the octavo manuscript titled “Poems On Several Subjects, Written By Ardelia” (begun circa 1690), now at the Northamptonshire Record Office, U.K. Although Finch’s informal hand is unusual, prompting scholars to assume this was the reason Heneage became her amanuensis, W. J. Cameron and Alexander Lindsay have argued that pages 1 to 87 of the octavo are in Finch’s fair copy hand. 5 5 Cameron, “Anne, Countess of Winchilsea: A Guide for the Future Biographer,” unpublished thesis (Victoria University of Wellington, NZ, 1951), 69, 73; Lindsay, Index of English Literary Manuscripts, volume III, part 4 (London, 1997), 536. The regularity of spacing within the letters on each line and the elegance of the hand, especially in comparison with known examples of Finch’s hand, suggest that these first pages in the volume are the work of a professional scribe, however.66 Professor Alan Nelson, pers. comm. Heneage took over transcription of the octavo manuscript, beginning half way through page 87. Although the octavo manuscript was used later for drafting her ode “Upon the Hurricane” (completed 1704), Heneage stopped transcribing poems in the octavo (probably deemed too small to include all of her poems and her two plays) and began transcribing c. 1700 the works in the folio manuscript “Miscellany Poems With Two Plays by Ardelia” (now housed at the Folger Shakespeare Library) where we find corrections in Finch’s hand.

The early eighteenth century witnessed significant changes in the Finches’ circumstances. After Heneage’s arrest for Jacobitism in 1690, the pair was confined to England, which must have encouraged their discretion as well as their desire to avoid surveillance. 7 7 Paul Monod, Jacobitism and the English People, 1688-1788 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 284. In a letter to antiquarian William Charlton in 1701, Heneage refers cryptically to “my confinement to a country life.”88 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 73; BL Sloane MS 3962, 284-287 In many works in the octavo and folio volumes the pro-Stuart and Jacobite allusions are discreet but persistent, and topics such as betrayal, the loss of principle, and the inevitability of failure, reveal Finch’s preoccupation with James’s fate (see, for example, on this site Finch’s paraphrase of psalm 135 , which suggests a correspondence between exiled Jews and the internal exile of James’s supporters. Heneage’s support of the Nonjuring bishops, who had refused the oaths of allegiance to William and Mary and renunciation of James, further identified the couple as Stuart adherents. James died on September 5, 1701, however, releasing Heneage from suspected loyalty to the exiled king if not to his heir, James Francis Edward. William’s illness and unpopularity influenced Heneage’s decision to stand for Parliament in December 1701, as Jacobites hoped to support a Stuart restoration after William’s death. Although unsuccessful in this and two later attempts (in 1705 and 1710), Heneage evidently felt free to attempt a return to public affairs. 9 9 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 89-91; Basil D. Henning, The House of Commons 1660-1690 (London: Secker and Warburg, 1983), 2:324. By 1708, the Finches resumed living in London and by the end of the decade, they settled in Cleveland Row, bordering St. James’s Palace,1010 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 91. where they lived for most of their remaining life.

Earl of Winchilsea

The Finches experienced another personal revolution on August 4, 1712, when Charles Finch died suddenly, leaving Heneage to succeed him as fifth earl of Winchilsea. (Heneage is sometimes counted as the fourth and sometimes as the fifth Earl of Winchilsea because the first person to hold this peerage was a woman1111 See McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 27.; the Dictionary of National Biography refers to Finch’s husband as the fifth earl.) Heneage refused the oaths of allegiance required to take his seat in the House of Lords, but otherwise the Finches gained assured social status as earl and countess. The one print volume of her work supervised by Finch and her husband appeared shortly after Heneage inherited his title: Finch’s Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions, was printed by John Barber in 1713.

Heneage’s accession, however, placed the Finches in grave financial straits. Charles’s sister, Marianne Herbert, and her husband sued the Finches in the Court of Chancery, contesting the late earl’s estate. Litigation dragged on from July 1713 until February 1720, as Heneage worked first through the Herberts’ case and then through creditors’ claims that kept Eastwell in receivership from November 1716 until August 1718.1212 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 99. In spite of these financial and legal difficulties, the Finches continued their support for fellow Nonjurors: in 1713, Heneage witnessed the consecration of two Nonjuring bishops, one of whom, Samuel Hawes, became their permanent guest at Eastwell after he was deprived of his living. They also befriended the Reverend Hilkiah Bedford (1663-1724), a Nonjuring clergyman imprisoned from 1714-1718 on the false charge of writing a Jacobite treatise (George Harbin’s The Hereditary Right of the Crown of England Asserted ). On his release, Bedford became Heneage’s chaplain.1313 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 184-185.

Heneage lived for six years following his wife’s death in 1720. In the blank page facing the month of August in his Riders (1723) British Merlin diary, HF wrote the following:

5 - 1720. - At 9. of the clock at night my most dear Wife of blessed memmory went to HeavenShortly before or after her death, Heneage had turned to preserving fifty-seven poems composed by his wife that were not collected in previous volumes. This final manuscript, now known as the Wellesley manuscript (housed in the Special Collections of the Wellesley College Library), appears to be written in two hands: the first unidentified and the second Heneage’s. In his last years, Heneage remained close to his many relatives and friends, corresponding with Lord Hertford and his family and pursuing archaeological research with his then-chaplain, the Rev. John Creyk. 14 14 Deborah Kennedy, Poetic Sisters: Early Eighteenth-Century Women Poets (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2013), 30-31; Heneage’s letters to Dr. John Stukeley in John Nichols, ed., Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century , 2 vols. (London, 1817), 2:769-785. Before and after Finch’s death, Heneage pursued antiquarian studies and absorbed himself in Kentish antiquarian lore, becoming involved in local archaeology and collecting ancient medals. Heneage’s manuscript volume titled “A Description of My Athenian Medals with Observations upon Them” (dated 1702) is preserved in The Bodleian Library. He joined the Society of Antiquaries, serving as vice-president from 1724 until his death.1515 Henning, The House of Commons, 2: 234. He corresponded with the scholar Dr. William Stukeley, “the central figure of early eighteenth-century archaeology,” and such fellow antiquarians as his brother-in-law Lord Weymouth and great-nephew-in-law Lord Hertford about their shared interests. 16 16 Stuart Piggott, William Stukeley: An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary, rev. ed. (1950; repr., New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 13; McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry , 73; Henning, The House of Commons, 2:324. Heneage and Stukeley were members of an antiquarian club called the “Society of Roman Knights,” focused on the study of Roman Britain, and by 1721 he and Stukeley began research on British coins for Metallographia Britannica.1717 Piggott, William Stukeley, 53, 71.

Heneage continued to suffer periodic attacks of gout, an early appearance of which had been recorded in Finch’s “The Goute and Spider,” included in the Folger folio. His death on September 30, 1726 resulted from what was described as an inflammation of the bowels.1818 Henning, The House of Commons, 3: 324. In 1758, his books were offered for sale in a catalog issued by Thomas Osborne. Although mingled with several other libraries, the list suggests a man of wide-ranging interests, piety, and modern as well as ancient learning ( The Second Volume of T. Osborne’s Catalogue of Books, Containing the Libraries of The Right Hon. Heneage Finch, Earl of Winchelsea . . . And many other Persons . . . [London, 1758]).

Sources

Much of the biographical information about Heneage Finch is found in Barbara McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry: A Critical Biography (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992); Barbara McGovern, “Anne Finch,” the Oxford DNB Online; and Sonia P. Anderson’s entry for Heneage’s father, “Heneage Finch, third earl of Winchilsea,” the Oxford DNB Online. On Heneage’s antiquarian activities, see Stuart Piggott, William Stukeley: An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary, rev. ed. (1950; repr., New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985); and on Heneage’s circle, see Basil D. Henning, The House of Commons 1660-1690 (London: Secker and Warburg, 1983).

We thank Deborah Kennedy for her help with locating the reproduction of Heneage Finch’s portrait.

Rachel Bowman, Claudia Kairoff, Jennifer Keith

1 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 29.

2 MS F.H. 282 in the Northamptonshire Record Office.

3 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 30.

4 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 58-60.

5 Cameron, “Anne, Countess of Winchilsea: A Guide for the Future Biographer,” unpublished thesis (Victoria University of Wellington, NZ, 1951), 69, 73; Lindsay, Index of English Literary Manuscripts, volume III, part 4 (London, 1997), 536.

6 Professor Alan Nelson, pers. comm.

7 Paul Monod, Jacobitism and the English People, 1688-1788 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 284.

8 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 73; BL Sloane MS 3962, 284-287.

9 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 89-91; Basil D. Henning, The House of Commons 1660-1690 (London: Secker and Warburg, 1983), 2:324.

10 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 91.

11 See McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 27.

12 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 99.

13 McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry, 184-185.

14 Deborah Kennedy, Poetic Sisters: Early Eighteenth-Century Women Poets (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2013), 30-31; Heneage’s letters to Dr. John Stukeley in John Nichols, ed., Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century , 2 vols. (London, 1817), 2:769-785.

15 Henning, The House of Commons, 2: 234.

16 Stuart Piggott, William Stukeley: An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary, rev. ed. (1950; repr., New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 13; McGovern, Anne Finch and Her Poetry , 73; Henning, The House of Commons, 2:324.

17 Piggott, William Stukeley, 53, 71.

18 Henning, The House of Commons, 3: 324.