Finch's Songs in Performance

“A Song” (’Tis strange, this heart within my breast)

See The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea: Volume 1: Early Manuscript Books (hereafter CEAF1), pp. 73–74, 510–12.

One of the Featured Poems in this Digital Archive, the song was composed no later than 1691; its first known printing is in Vinculum Societatis, or The Tie of Good Company (1691, Book 3, p. 15). 1 In its collection of songs, Vinculum Societatis provided thorough-bass for harpsichord and other instruments and was no doubt intended for the private gatherings and performances popular in that era. Raphael Courteville’s setting of this piece in Vinculum Societatis includes only the first eight lines of the poem. The music is a sensitive setting of the text in G-minor. The opening motive of a rising fifth, on the words “’tis strange,” is repeated later, under the words “in vain,” creating a musical as well as textual link between the two lines. The somber mood is reinforced by sequences of sighing appoggiaturas in the vocal line, as well as the expressive and unexpected harmonic turns in the basso continuo accompaniment. Listen to the performance of “’Tis strange.”

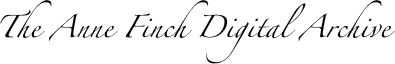

“A Moral Song” (Wou’d we attain)

See CEAF1, pp. 77–78, 518–19.

The song was composed no later than c. 1696. 2 “A Moral Song” also appeared in Finch’s Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions (1713) and later in The British Musical Miscellany, or, The Delightful Grove ([1735], 4: 88), with the musical setting included here by William Boyce (bap. 1711, d. 1779) (see Figure 1).

A composer of numerous songs and pieces for the theatre in addition to his well-known symphonies and sacred choral works, Boyce served as composer to the Chapel Royal from 1736 and as master of the king’s music from 1757. 3 The title “A Moral Song” identifies the poem as distinct from contemporary secular lyrics concerned with less edifying themes. “A Moral Song” is unusual in addressing love, the typical secular song topic, from the perspective of strict morality: peace of mind accompanies only total refusal.

The musical setting here is a charming air in triple meter. The melody, in four phrases, is used twice, serving as an elegant vehicle for the delivery of the text, but it is not particularly responsive to the meaning of the text as it unfolds. Listen to the performance of “A Moral Song.”

“A Song” (Strephon, whose Person evr’y grace)

See CEAF1, pp. 77, 516–18.

The song was composed no later than c. 1696. 4 Several collections reprinted the song, including The Hive: A Collection of the Most Celebrated Songs (1727), where it is titled “The Wit and the Beau” (2: 120), with a setting by Scottish composer James Oswald, who has written a simple strophic melody that is played four times, with different lines of text sung each time. Listen to the performance of “The Wit and the Beau.”

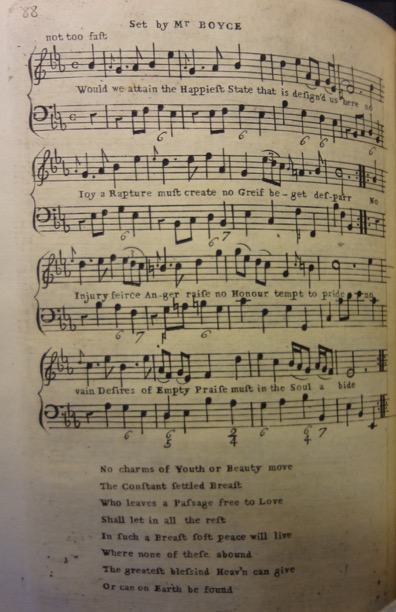

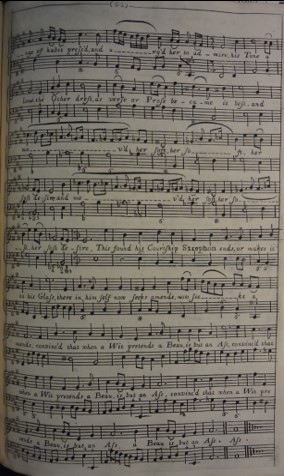

The song’s first known printing is in A Collection of Songs for One Two and Three Voices. . . . Compos’d by Mr. John Eccles, Master of Her Majesty’s Musick (1704), pp. 61–62 (see Figure 2). As the 1704 musical setting indicates, Finch’s skill was recognized by John Eccles (c. 1668–1735), the major English theatre composer following Purcell. 5

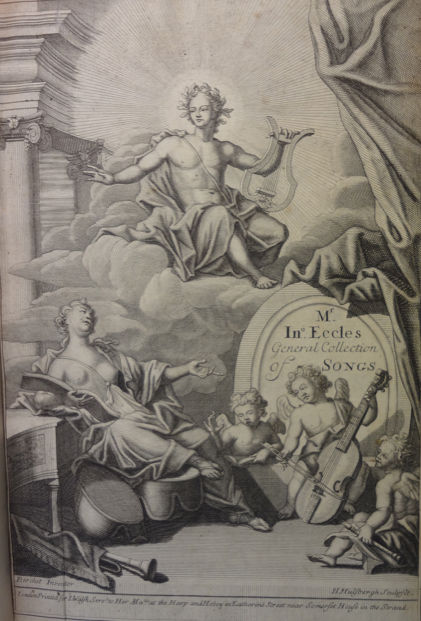

Eccles often set songs for the popular singer-actress Anne Bracegirdle (bap. 1671, d. 1748), to whom he dedicated this piece (see Figure 3). The beau and the wit, and their contest over a heroine’s heart, echoes the plot of many Restoration and early eighteenth-century comedies. In Sir George Etherege’s The Man of Mode (1676), for example, the oblivious Sir Fopling thinks the clever hero, Dorimant, should acquire a looking glass for his room: “In a glass a man may entertain himself,” he urges, “Correct the errors of his motions and his dress.” 6 Like Etherege’s fop, Strephon will have to court himself in his mirror after Sylvia loses her heart to his witty rival.

Figure 3 Pages 61 and 62 of John Eccles's setting of Finch's "Strephon, whose Person" (The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Harding Mus. E 13, folio).

Eccles’s composition is much more responsive to the text than the Oswald setting. The song unfolds freely, using various rhetorical devices to underscore the meaning of the poem. Eccles asks the singer to repeat certain words and phrases for emphasis, and changes meter and harmonic underpinnings in an agile and dramatic manner. Listen to the performance of “Strephon whose Person ev’ry Grace.”

“A Song” (Love, thou are best)

See CEAF1, pp. 72, 504–507.

The song was composed no later than 1693: that year it was printed in The Gentleman’s Journal (vol. 2, October 1693, p. 330) and in Thomas Wright’s The Female Vertuoso’s, a play dedicated by Wright to Finch’s nephew Charles Finch, Fourth Earl of Winchilsea. “Love, thou art best” is today Finch’s best-known song. In the play, the hero Clerimont accompanies the song as his own composition in a successful bid for permission to marry the heroine, Mariana. Raphael Courteville’s setting of the poem was printed in A Collection of New Songs Sett by Several Masters (1695?), where it appears as the seventh of eight unpaginated songs. 7 Courteville sets the text as a light, galant minuet in A-B-A da capo form. The harpsichord accompaniment, as in virtually all song settings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, is limited to “basso continuo” or “figured bass,” wherein only the left-hand melody is notated, and the harmonies or countermelodies in the right hand are to be improvised, according to the shorthand harmonic indication, or “figures,” placed above or below the written left-hand line in the score. Listen to the performance of “The Prerogatives of Love.”

Better known is Henry Purcell’s setting of this same work, printed in Comes Amoris; or The Companion of Love (Fifth book [1694], p. 35) and still occasionally performed. 8 We do not know why Purcell decided to compose a duet version of the same song; perhaps its current popularity inspired his decision to increase its performance options. Purcell, like most late-seventeenth-century composers, altered lyrics when setting poems: as Franklin Zimmerman noted, “for purely musical reasons he often repeated words, phrases, even whole lines in such a way as to upset poetic balance altogether.” 9 Finch’s lyrics, as here, were not exempted from this practice and were usually revised somewhat to suit her composers’ interpretations. Purcell’s setting of the text offers a striking contrast to Courteville’s. Choosing to compose it for two soloists offers Purcell more polyphonic possibilities and contrasts in texture. It is in a minor key, with gentle free imitation between the solo voices which often quickly reverts to extended passages in parallel thirds or sixths, lending an Italian aura to the music. Purcell also employs a playful “hocket” technique at times, such as on the word “that” in the final section, in which the word bounces back and forth between singers. Teresa Radomski is joined in this performance by soprano Mary Mendenhall. Listen to the performance of “Love, thou art best.”

“A Song” (Persuade me not, there is a grace)

See CEAF1, pp. 71, 502–503.

One of the Featured Poems in this Digital Archive, the song was composed no later than c. 1696. 10 Ten years after Finch’s death, “A Song” was printed in The Musical Miscellany (1730, 4: 170–71), unattributed, as “Love and Musick.” As with her other printed lyrics, Finch’s song participated in the fashion for printed music that allowed singers and musicians to perform songs at private gatherings as well as public recitals. In The Musical Miscellany, Finch’s song is printed with instructions that it be sung to a tune “by a Gentleman at Oxford,” attached to the preceding poem. The musical setting here is strophic, with the same music heard three times under different lines of the text. The melody is a folk-like air in triple meter, which offers an opportunity for improvised variations on each repeat, as in this performance. Listen to the performance of “Persuade me not, there is a grace.”

“A Sigh”

See CEAF1, pp. 356, 686–88.

The song was composed no later than c. 1702. 11 The first known printing is in the 1703 miscellany Poems on Several Occasions (87–88). There it was followed by a parody, “The Sigh Revers’d” (88–89), in which the sigh is replaced with a fart. Finch did not include “A Sigh” in Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions, her 1713 authorized print volume, perhaps not wishing to associate herself with a poem that had been crudely parodied.

“A Sigh” was among Finch’s most frequently copied and reprinted poems: in addition to the first known printing of 1703, cited above, the poem appeared in Poems on Affairs of State (1704), Delarivier Manley’s Court Intrigues (1711) (almost certainly unauthorized), and Richard Steele’s Poetical Miscellanies (1714); it continued to be printed in collections into the nineteenth century. Many composers recognized the potential of “A Sigh” as a lyric suitable for their music. The settings include this one by composer and harpsichordist John Sheeles (1695?–1764) in The Musical Miscellany (1730), 3: 138. 12 The musical setting is strophic, with the gracious minuet-like melody serving for each stanza of the poem. This performance adds an improvised instrumental interlude before the final stanza. Listen to the performance of “A Sigh.”

Claudia Thomas Kairoff with Peter Kairoff

1 See CEAF1: 510–12.

2 See CEAF1: 518–19.

3 Robert J. Bruce, “Boyce, William,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online.

4 See CEAF1: 516–18.

5 David G. Golby, “Eccles, John,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online.

6 Etherege, George, The Man of Mode, or Sir Fopling Flutter (1676), 4.2, 91–92, 95, in The Plays of Sir George Etherege, edited by Michael Cordner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

7 See Ian Spink, “Courteville, Raphael,” in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online; and CEAF1: 504–506.

8 See Robert Thompson, “Purcell, Henry” in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online.

9 Franklin B. Zimmerman, “Sound and Sense in Purcell’s ‘Single Songs,’” Words to Music: Papers on Seventeenth-Century Song Read at a Clark Seminar December 11, 1965, ed. Vincent Duckles and Franklin B. Zimmerman (Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 1967), p. 57.

10 See CEAF1: 502–503.

11 See CEAF1: 686–88.

12 “John Sheeles,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology, Canterbury Press, accessed May 30, 2018; https://hymnology.hymnsam.co.uk/j/john-sheeles.